I recently wrote a feature for the in-house Cutler & Gross magazine about the manufacturing of their glasses, including an interview with CEO Majid Mohammadi. It is reproduced below. C&G are in an interesting position, sitting between the very large, mass manufacturers and the smaller boutiques in Germany, Japan and the US.

Making our way home

As Cutler and Gross opens its London atelier, Simon Crompton considers the state of the eyewear industry and the enduring significance of craftsmanship and materials in the production of frames

Apparently, the latest thing in modern security equipment is smoke bombs; as soon as an alarm goes off, these devices fill the entire building with smoke. No one can see anything, so no one can steal anything. The intruders have little option but to stumble back the way they came and make a run for it.

Cutler and Gross’s new atelier in west London might seem like an odd place to be fitted with smoke bombs: two floors of a fairly anonymous building in Neasden occupied by a handful of designers, developers and engineers. There is some valuable glasses-making equipment, but that’s not the reason for the security. The really important things are the prototypes.

The new atelier opened in February this year and brings together the best elements of Cutler and Gross design. The first Cutler and Gross shop opened in Knightsbridge in 1969, and the Italian production facility was established in 2007.

‘Italians are wonderful craftsmen and they are obsessive about what they do,’ says Majid Mohammadi, CEO of Cutler and Gross, ‘though they’re perhaps not as passionate about management’. As an example, he recalls a moment during his career as a chartered accountant when he walked past a roomful of Italians having a meeting. ‘Everyone was screaming at each other, trying to make themselves heard. One guy was even standing on the table, stamping his foot, but no one was paying any attention.’

Majid values Italian craftsmen for their focus, which makes them great technicians. But London has arguably the brightest design minds in the world, so senior Italian staff will work in rotation at the London atelier, helping to bring practical solutions to the new design ideas their British colleagues are coming up with. Members of the London team will also visit Italy to learn more about how glasses are made.

‘That cross-pollination is crucial to a brand like ours, which needs to remain innovative yet produce wearable, timeless designs,’ says Majid. ‘Only when a designer sees the production process does he realise why certain things are made a certain way.’ Adding a fraction of a millimetre to the thickness of an arm, for example, can make a big difference to how well a frame wears over time.

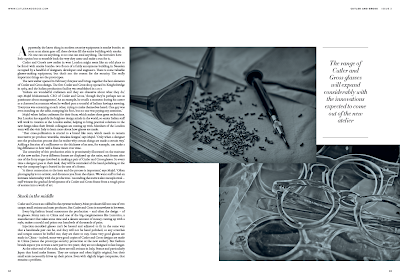

The centrality of this production ethic is prominently illustrated on the staircase of the new atelier. Forty different frames are displayed up the stairs, each frozen after one of the forty stages involved in making a pair of Cutler and Gross glasses. So every time a designer goes to their desk, they will be reminded of the hand-polishing or the way the company logo is buried in the arm of a frame.

‘A direct connection to the item and the process is important,’ says Majid. ‘Often photography is too artistic, and distances you from the object. We want staff to feel an intimate relationship with the production.’ Ascending the stairs is also metaphorical – staff witness the gradual development of a Cutler and Gross frame from a rough piece of acetate into a work of art.

Stuck in the middle

Cutler and Gross is an oddball in the eyewear industry. Most producers fall into one of two camps: small artisans and mass producers. But Cutler and Gross is somewhere in between.

Every big fashion brand outsources the production – and often the design – of its glasses. Many turn to China and one of the big conglomerates like Luxottica, a manufacturer that takes some time and a decent amount of money coming up with a style, makes a mould and prints out hundreds of thousands of pairs.

Injection-moulded glasses can’t be heated and adjusted to fit in the same way that a handmade pair can be, and they will not be hand polished, so any scratches and scrapes cannot be buffed out; they are there to stay. Some very good glasses are made in China – indeed, some very good copies of Cutler and Gross designs are made in China (hence the prototype security protection at the new atelier). But fashion brands expect you to want a new pair in two years; they are not designed to last longer.

At the other end of the scale, there are still artisans in Italy, France and particularly Japan that hand make frames. They are unique and often highly original, but their small scale necessarily drives up their prices. Even with slightly larger companies, that remains a problem.

Although Cutler and Gross makes thousands of frames a year, this is nothing compared to the millions churned out for the mass market of trend-driven sunglasses. Each Cutler and Gross frame takes four weeks to make, and their individually crafted nature means there is a higher proportion of wastage. ‘When the hinges are screwed in by hand, part of the frame might be scratched. So then it has to go back to be polished again. You do that enough times and there will be a few that have to go in the bin,’ says Majid.

Perhaps more unusual than Cutler and Gross’s size is its Italian production. Until five years ago, the frames were made in several factories in France, Italy and Japan. Then the company took the opportunity to buy a bigger facility in Cadore, the ‘eyewear valley’ of Italy. ‘That was a game changer for us,’ says Majid. ‘It finally put everything in one place and enabled us to exert far greater control over the production.’

Control is a running theme at Cutler and Gross, which does its own photo shoots, marketing and – most unusually in the eyewear industry – distribution. Cutler and Gross never has sales; its customers understand the luxury market and buy into the price point that such exclusivity commands.

A big catalogue getting bigger

The archive of Cutler and Gross frames stands at over 1,000, multiplied by four when taking into account alternative colours and materials. A fraction of that is in constant production, while the vintage selection is available exclusively in Cutler and Gross shops and from the brand’s own website.

Startlingly for a company of their size, it will also readily make bespoke pairs, varying just the colour or the fundamental shape of the frame itself. As with many areas of Italian manufacturing such as suits and other menswear, this bespoke or made-to-measure service is enabled by the fact that all the glasses are created individually. There are plenty of Cutler and Gross customers who are prepared to invest in an exclusive design, and who will happily wait for their frames should certain materials need to be specially acquired.

The range of Cutler and Gross glasses will expand considerably with the innovations expected to come out of the new atelier. Precursors include models where two or three layers of acetate have been cut at different levels to leave a textured surface on the front of the frame. One example, which recreates part of a Piet Mondrian painting, shouts ‘rock star’.

Another creative development is the Precious Metal Collection, for which Cutler and Gross employs palladium and silver – as well as 18-carat gold, which gives an unexpectedly warm and luxurious feel to the frame. And, along with many others in the industry, the company is working with materials like titanium. ‘It’s all about quality though, that’s the important thing,’ says Majid. ‘Our normal steel is more expensive than the titanium most people use.’

He dismisses decorative options, like adding diamonds to a frame. ‘We want to do something more original, to push boundaries. Someone recently said that the reason they loved Cutler and Gross was because the brand is so strong; that if we were doing something, everyone would assume it was the best new thing. He said we could make glasses out of cork and everyone would follow. I don’t think we’ll ever go that far, but we certainly want to be innovative.’

With the potential for such game-changing innovation, perhaps smoke bombs are a sensible choice after all.

Hi Simon,

I’m interested in learning more about frames, both for spectacles and sunglasses. I’d appreciate it if you wrote an article on the subject. You hint at artisans in Italy, France and Japan that hand make frames. It would be useful to elaborate on them. You can further advice on how IP & competition attorneys are expected to dress.